GAB welcomes this Guest Post by Noam Kozlov, an honors graduate of Hebrew University with an undergraduate degree in Economics and Philosophy and an LL.B. A clerk for Israeli Supreme Court Justice Yosef Elron during the 2024/2025 term, he is now pursuing an LL.M. at the Harvard Law School.

For decades, the United States has spearheaded the global fight against transnational corruption. Its Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, the first statute to outlaw foreign bribery, led directly to the 1997 OECD Anti-Bribery Convention which requires all wealthy nations to outlaw foreign bribery. The US has also been the leader in prosecuting foreign bribery cases, bringing more than the rest of the world combined.

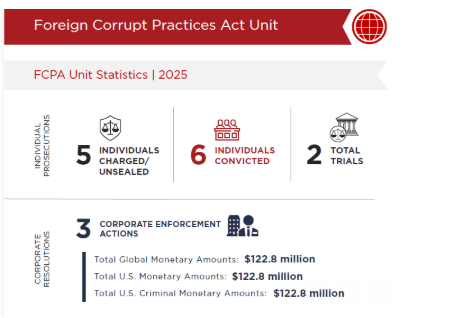

The Trump administration’s February 2025 pause in FCPA enforcement, and subsequent new policy narrowing its scope, have created a crisis in the enforcement of this fundamental global anticorruption norm. What nation has the reach and the resources to take over from the US?

At the same time, there could be a bright edge to the shadow cast by the US retreat. The crisis could force the international community to move away from reliance on a single dominant country and toward a more equitable model of enforcement, one based on shared responsibility through prioritizing the sharing of proceeds and empowering institutions in nations where bribes were paid; an approach that would advance the restitutive objectives of anticorruption enforcement more effectively than the US-centric model ever could.

Continue reading