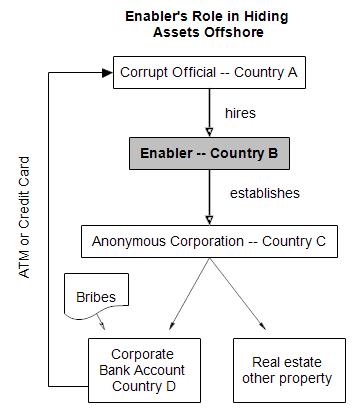

Central Asia Due Diligence and the Uzbek Forum for Human Rights have identified the latest fallout from the Trump Administration’s destruction of American institutions devoted to fighting global corruption. The governments of Belgium and Uzbekistan have each pocketed $108 million in stolen assets that should have gone to the people of Uzbekistan.

In this just released paper, the two human rights NGOs explain how the demise of the Department of Justice’s Kleptocracy Asset Recovery Initiative allowed the two governments to ignore provisions in the UN Convention Against Corruption and the principles of the Global Forum on Asset Recovery that together bar assets stolen by a corrupt official from being kept by the government of the country where the official stashed them or returned to the official’s corrupt cronies.

Lawyers for the Initiative had designed a sophisticated process (details here) to see the $216 million in bribes to former Uzbek first daughter Gulnara Karimova found in Belgian banks DoJ would go to the UN trust fund overseeing development programs in Uzbekistan. With the Initiative’s demise, the Belgian and Uzbek governments apparently saw no reason they should not divvy up the money between them.

So thanks to the Trump Administration, Belgium, one of the world’s wealthiest countries, is now $108 million wealthier, and Uzbek’s leaders, several Gulnara’s accomplices, now have $108 million to spend keeping themselves in power. Meanwhile, the citizens of Uzbekistan, GDP per capita $3,500, scrape by.