In a forthcoming article in the Notre Dame Law Review, Professors Reid Weisbord of Rutgers Law School and Stewart Sterk of the Cardozo Law School examine the trade-offs posed by requiring the public disclosure of the beneficial owners of real estate. While promoting real estate ownership transparency and curbing criminals’ ability to use anonymously-owned real estate, there are clear disadvantages to making the home addresses of all citizens public, the recent murder of a federal judge’s son at the family home by a disgruntled litigant who found their address online the most patent.

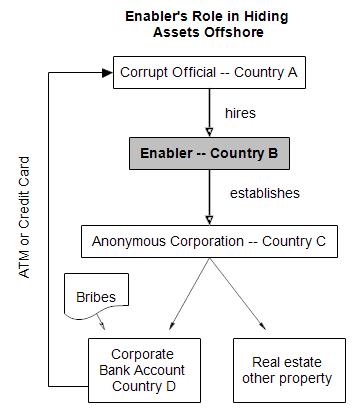

As Professors Weisbord and Sterk explain, a common law trust is one way citizens can keep their home address private, but as they also say, the Pandora Papers shows how easy it is for corrupt officials and criminals of all kinds to use a trust to thwart law enforcement. As Congress considers legislation to end trust abuses, the two urge lawmakers not to lose sight of the downsides of requiring the unrestricted public disclosure of the home addresses of all citizens. At GAB’s request, Professor Weisbord summarized the relevant portion of their article for GAB readers. The Notre Dame article and an earlier article by Professor Weisbord prompted by publication of the Panama Papers should be required reading for those struggling with how to ensure criminals cannot hide from law enforcement through the use of anonymous corporations, trusts, and other “offshore vehicles,” while protecting judges, victims of domestic or sexual abuse, or others with a legitimate need to keep their home address private.

On October 3, 2021, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (“ICIJ”) published the findings of a massive worldwide investigation that painstakingly reviewed nearly 12 million confidential financial documents, a collection now known as the Pandora Papers. In keeping with its prior bombshell investigations, including the Panama and Paradise Papers, the ICIJ has once again exposed a trove of secret financial transactions by a global cohort of world leaders, politicians, and billionaires who have offshored assets by covertly acquiring or storing property in foreign countries. There can be legitimate reasons for individuals to secretly acquire property abroad, but such transactions are also notoriously used to launder money and defraud creditors or tax collectors by evading the jurisdictional reach of the individual’s domestic legal system.

Continue reading