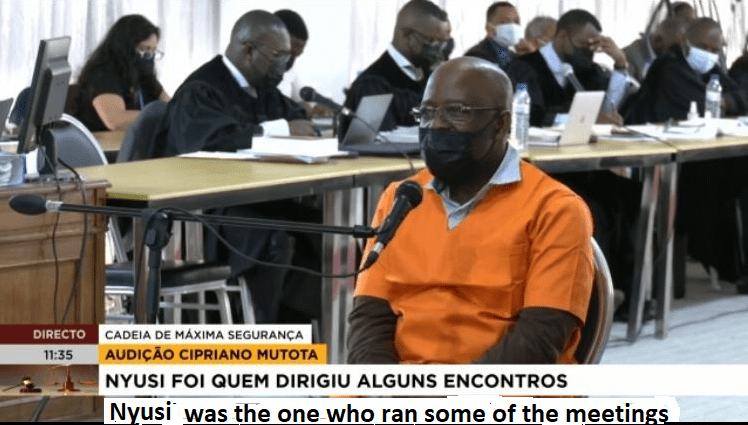

The government of Mozambique took two hits at the second day of what could well be the corruption trial of the decade. Defendant Cipriano Mutota, a former intelligence official, testified that both the country’s current president and his predecessor were deeply involved in the corruption, a scheme where officials approved $2.1 billion in secret loans for dodgy projects in return for $150 million in bribes. His gripping testimony, captured in a screen grab circulating on Mozambican social media, appears below.

Separately, the Budget Monitoring Forum, or FMO after its initials in Portuguese, has filed an emergency motion to prevent South Africa from extraditing Manual Chang, who signed off on the loans as Finance Minister, to Mozambique. Chang has been jailed in South Africa for two years pending the government’s decision on whether to extradite him to the U.S. or Mozambique. Both want him, the U.S. because American investors lost millions thanks to the secret debts, Mozambique to stand trial for his role in the corruption.

The government of South Africa has agreed to delay returning Chang to Mozambique pending a hearing on its legality Friday at 10:00 AM. Along with South Africa’s Minister of Justice, the government of Mozambique will appear and argue in support of the decision. FMO’s draft order, which the court accepted and issued, is here.

FMO filed the emergency request Tuesday evening after the South African government refused to consent to a brief delay in Chang’s return to allow an orderly consideration of whether the decision complied with South African and international law. In its filing, the group, an umbrella organization whose 22 civil society organizations serve virtually every impoverished or low income Mozambican, argues that the evidence shows the government will not really put such a senior figure on trial for corruption. Or if it does, he will get a most a slap on the wrist for a scheme that threw millions into poverty and by one estimate shaved $10 billion off the GDP.

FMO cites a previous Mozambique extradition request (here) that had every appearance of a put-up job, initiated not to bring Chang to justice but from a fear that were he sent to the U.S. he would spill the beans on cronies in return for leniency. Rumors circulating in Maputo that Chang’s relatives have planned a lavish welcome home party have only stoked concerns he has little to fear from a trial in Mozambique.

FMO chair Adriano Nuvunga has called South Africa’s decision to send Chang to Mozambique, “a victory of impunity” and has urged “all southern Africa CSO movements to come together to stop the triumph of impunity.” FMO’s papers seeking a temporary delay in Chang’s return pending a full hearing are here. The Gauteng Division of the High Court may act on the request as early as Wednesday morning South African time.