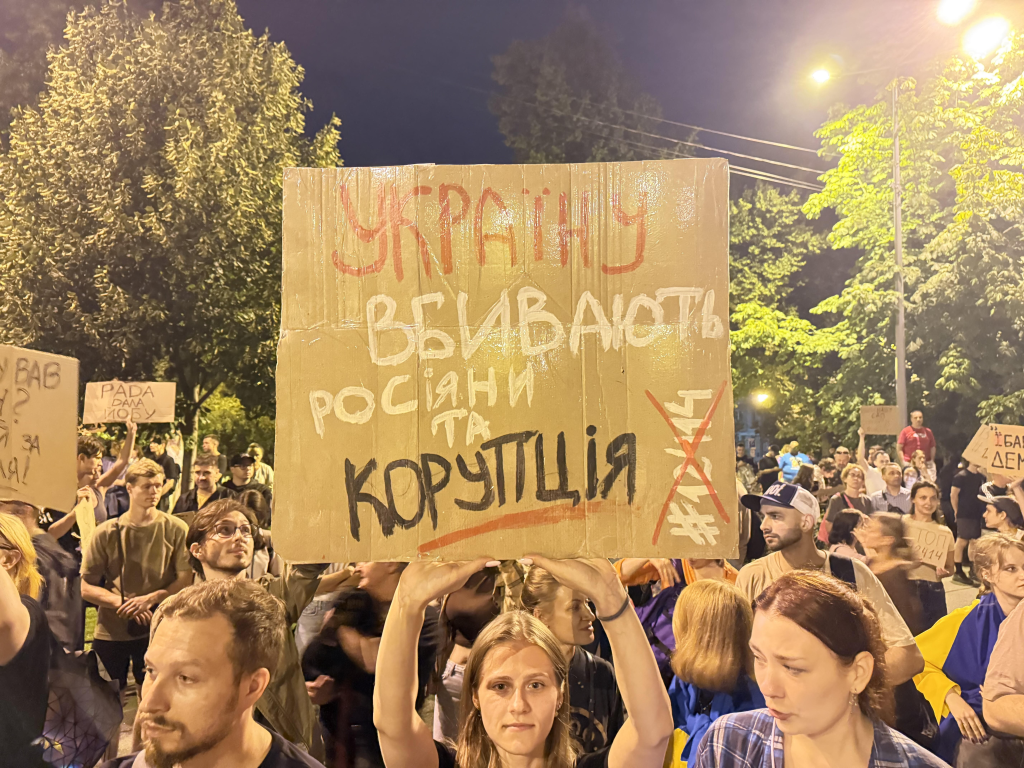

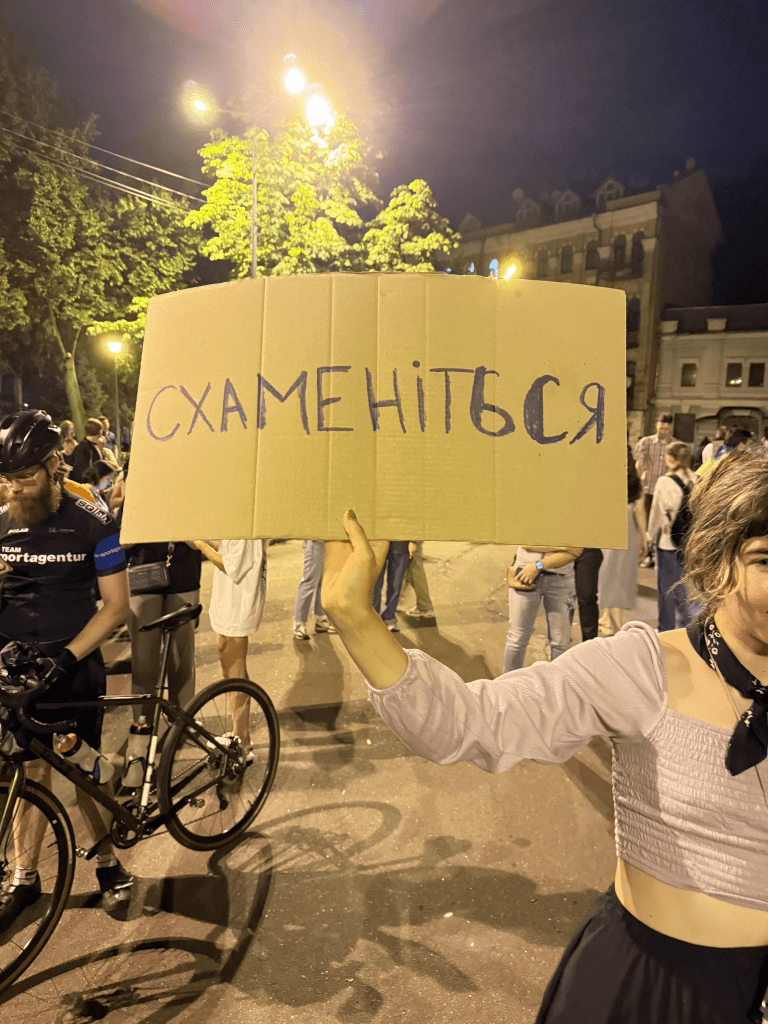

On July 22 Ukraine’s parliament approved without debate or warning legislation sharply curbing the independence of Ukraine’s corruption fighting agencies. Nine days later it okayed a second bill largely repealing the curbs. In between were massive demonstrations by citizens protesting the July 22 law and threats by the European Union to cut financial support.

Ukraine’s Institute for Legislative Ideas today published a report offering lessons from these events. The think tank’s analysis explains who and what was behind the attempt to defang the nation’s anticorruption agency and special corruption prosecutor and how the sudden backtracking is likely to affect Ukraine’s fight against corruption. Along the way the report provides a careful legal analysis of the July 22 legislation, what the second bill repeals and what it leaves intact; the stated reason for the July 22 law (cleanse the agencies of “Russian influence”); the real reason for its passage (investigations were getting too close to those in power), and what civil society and international partners must do to ensure there is no further effort to undermine the fight.

Critical reading not only for those concerned about corruption in Ukraine but for those in other nations where a transnational coalition is working to keep the corruption fight on track.

The English text of the report is here.