Thanks to Jason Sharman of Cambridge University and dodging shopping fame, those who didn’t attend last January’s conference “Empirical Approaches to Anti-Money Laundering and Financial Crime” are in luck. He has produced an excellent summary of the papers presented at this, the now third annual AML conference jointly sponsored by the Bahamas Central Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank.

There are dozens if not hundreds of other AML conferences held each year. At these, bankers and their lawyers, accountants, and consultants flyspeck the latest rules, court decisions, and other matters germane to complying with AML laws and regulations. As well they should, for as AML Penalties chronicles in their weekly bulletin, fines for violations are beginning to creep upwards. Conference attendees are also constantly on watch for cheaper ways to meet their legal obligations; AML compliance costs for all financial institutions are currently estimated to exceed $200 billion per year.

Like the first two conferences, last January’s had a much different agenda than those devoted to compliance. Rather than asking “what are the rules” and “how can we comply,” it asked more fundamental ones: “Are the current anti-money laundering rules worth cost?” “Are they keeping dirty money out of the system?” “Are there more cost-effective ways of doing so?”

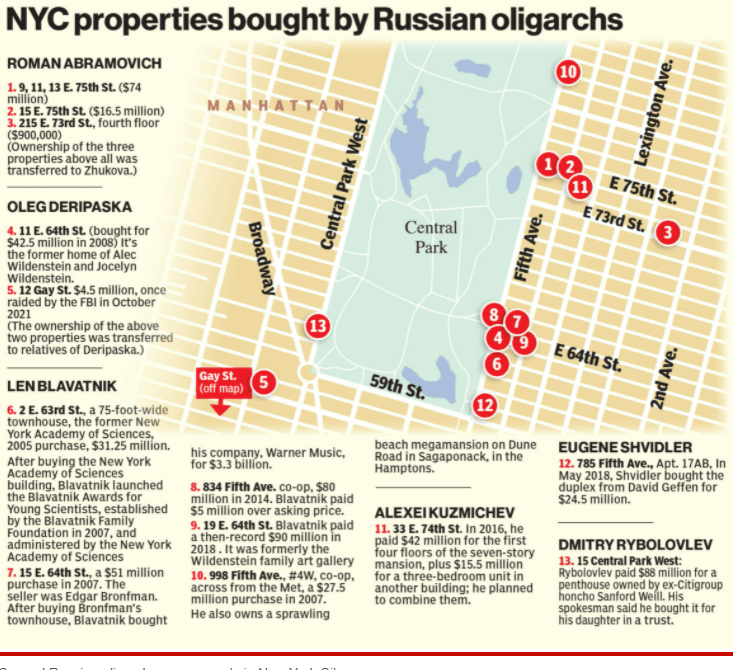

It is now clear that Russian oligarchs have had little trouble evading the current AML regime. Might this suggest the sponsors of the Bahamas conference are on to something? That the questions they are posing deserve at least as much attention as those discussed at the many compliance conferences?

Next year’s conference will be held January 19 and 20 in Nassau. The announcement is here.