“Populism” has been defined in many different ways, but the context in which the term is most frequently used today aligns with the definition proposed by Cas Mudde in The Populist Zeitgeist: “an ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite.’” This formulation certainly captures the political style of the leaders discussed at last month’s Harvard Law School conference on “Populist Plutocrats: Lessons from Around the World,” including Silvio Berlusconi in Italy, Thaksin Shinawatra in Thailand, Joseph Estrada in the Philippines, and (perhaps to a somewhat lesser extent) Alberto Fujimori in Peru and Jacob Zuma in South Africa. And it certainly captures the rhetoric of Donald Trump.

A couple of previous posts have provided an overview of the Populist Plutocrats conference agenda and information about the video recording (see here, here and here). In this post, I want to use the conference discussions as a jumping-off point for thinking more generally about how populism relates to systemic corruption—both as a consequence and as a cause.

Corruption as facilitator of populism

The rise of populist leaders is often fueled by widespread public disillusionment with existing institutions and dissatisfaction with chronic inequality. Populists seize on these frustrations and use them to rally public support against entrenched “corrupt elites” who do nothing to correct these dysfunctions. Populist leaders know how to capitalize on the public resentment of corruption; that is why a strong anticorruption posture is a staple in the populist’s arsenal of rhetorical devices. Populists cast professional politicians as corrupt elites (part of the “swamp” that Trump promised to “drain”). They distance themselves from the corrupt “establishment” (as when President Rodrigo Duterte, a former mayor of a city in the southern Philippines, promised to end the political domination of “Imperial Manila,” the country’s capital). They also highlight their status as “outsiders” (the way leaders like Berlusconi, Thaksin, and Trump emphasized their status as successful businessmen, not traditional politicians).

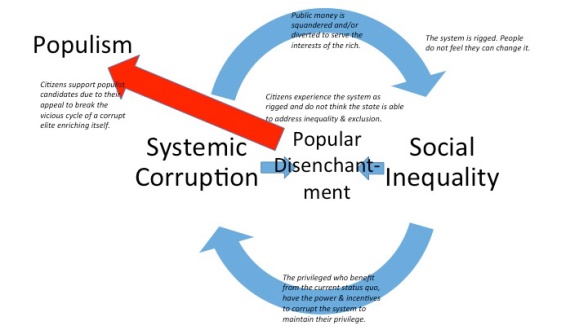

Furthermore, the environment of economic, political, and social inequality that nurtures populist movements is itself caused, or at the very least worsened, by widespread corruption. When rampant corruption undermines the effective delivery of basic services, it produces a sense of “failed expectations” among the public, and – as demonstrated in a study by Mattias Agerberg – moves them to favor populist politicians at the ballot box. As Transparency International’s Finn Heinrich wrote in a January 2017 report, corruption and social inequality “provide a source for popular discontent,” which in turn provides fertile ground for the seeds of populist politics to take root. Heinrich illustrated this dynamic through the following diagram:

Source: Transparency International/Finn Heinrich

Populism as facilitator of corruption

One of the striking things about the discussion at the Harvard Populist Plutocrats conference was the fact that not only do leaders like Berlusconi, Thaksin, Estrada, and Fujimori all share a common “origin story,” they also share a similar ending, as all of them eventually became entangled in corruption allegations after assuming power. Despite their professed anticorruption agenda, they resorted to the same corrupt machinations that they had attacked. Indeed, as Heinrich observed in his report, “the track record of populist leaders in tackling [corruption] is dismal; they use the corruption-inequality message to drum up support but have no intention of tackling the problem seriously.” It would seem that corruption does not merely exist at the onset of a populist regime’s rise to power, but continues during the populist’s reign, and often gets worse.

One of the keys to understanding how and why corruption continues to thrive in populist regimes is to consider the impact that a populist regime has on the democratic values that hinder corruption. As Professor Pippa Norris put it, populism “focuses power in the individual leader versus the party. It destroys and erodes … political trust… It also weakens accountability of the electorate. When you don’t have accountability, that often leads it open to other forms of power being abused and misused.” This seems consistent with the analysis of the participants at the Harvard conference: Leaders like Berlusconi in Italy and Thaksin in Thailand did not establish institutionalized, programmatic political parties, but instead built highly personalistic parties with themselves at the apex; Estrada in the Philippines convinced his friends in the business and entertainment industries to pull out their advertisements from media outlets critical of him; Fujimori in Peru closed down Congress and summarily sacked the entire rank of judges. These populist leaders have a tendency to convert their electoral mandates into almost boundless, unchecked, and concentrated power – a recipe for rampant and systematic corruption.

Understanding how populism both results from and results in corruption will help anticorruption advocates and those who seek to stem the spread of vile forms of populism across the world. The implication is clear: since corruption makes it possible for populist regimes to rise to power, and populist regimes foster systemic corruption, the mutually-reinforcing cycle can only be broken if both populism and corruption are arrested. The ouster of one populist leader will not prevent the rise of another if the corruption he or she leaves behind is not effectively addressed.

Reblogged this on Matthews' Blog.

Thank you for your thoughts, Ryan.

As for the need to address corruption to ensure that the ouster of one populist leader does not result in the rise of another: I feel like this is certainly true, but the practical reality is that policies to address corruption, especially the corruption of a populist regime, are influenced by many cross-cutting social, political and economic considerations, especially if the deposed leader still has popular backing. This complexity is compounded by the fact that having to deal with an inherited legacy of corruption may result in the need for austerity and other “unpopular” measures; which is fodder in the hands of the deposed populist regime to foster discontentment. Thus I do not feel like there is a one-size-fits-all solution to deal with “corruption and populism” as two sides of the same coin. In fact, like discussed at the Populist Plutocrats conference, sometimes what is needed may be a form of “benevolent populism”.

Ryan, really interesting post. I like how you linked the psychology of populism with corruption, and how these leaders play on certain biases against the “corrupt elites” in their rhetoric to inspire popular support. I think what’s striking about this concept for the U.S. is where the country falls in the cycle that you’ve laid out. While Trump hasn’t yet seen the same common end as the other leaders you mention, he is more than willing to fan the flames of populist tendencies in order to more deeply drive a wedge between the “pure people” and the “corrupt elite” and consolidate his own support. I think we’re also experiencing a version of the individual leader phenomenon that Professor Norris describes as well (illustrated by the near-constant GOP infighting). Perhaps in the U.S. at least, the institutions are strong enough to withstand this kind of pressure, instead of enduring the same fate as the other places you mention.

Pingback: The populist paradox – f-fr

Pingback: The populist paradox | PG-Intel

Pingback: The populist paradox - Randy Salars News And Comment

Pingback: The populist paradox – medicalbilling

Pingback: Social Economic Evils of Corruption | kenyaconfidential.com

Pingback: Social Economic Evils of Corruption – citizensagainstcorruptionk.org

Pingback: The populist paradox - Corruption Buzz