GAB welcomes this timely and important Guest Post on vote buying by Corina Rebegea, Non-Resident Fellow at the Accountability Lab, and Katie Fox, Eurasia Deputy Regional Director at the National Democratic Institute (NDI).

A common concern in combating vote buying is the ineffectiveness of typical awareness campaigns (here). An NDI program in Moldova suggests a more successful strategy: combine robust law enforcement with tailored, empowering public messaging. Rather than relying on fear or blame, this approach centers on voter dignity and institutional integrity, offering valuable lessons for combating electoral corruption worldwide.

Although the evidence comes from a single country, the Moldovan experience offers several lessons to inform future efforts to prevent vote buying:

- Negative messages tend to amplify distrust in elections, so the focus needs to shift from portraying elections as “stolen” to highlighting efforts to ensure their integrity.

- Identifying trusted actors in society is essential for raising awareness of what constitutes electoral corruption and conveying deterrent messages. In Moldova, the police emerged as an increasingly trusted force, potentially due to their involvement in anti-vote buying investigations.

- Messages that raise confidence and emphasize individual responsibility resonate better than those that blame or threaten citizens. Awareness-raising about the legal consequences will be well-received, but only among certain demographics, so an in-depth understanding of the different audiences is essential.

Electoral corruption remains a serious concern globally. Surveys consistently show that citizens perceive vote buying as a widespread practice across the world. The use of pre-electoral transfers—cash, goods, or favors—to influence voters is rooted in complex economic factors and deeply seated social norms, where parties leverage clientelist networks and exploit the short-term needs of financially vulnerable citizens. It is also often difficult to prosecute.

That is why democracy advocates have turned to public awareness campaigns – albeit with limited success. Campaigns aiming to reduce vote buying sometimes can break the reciprocity between voters and candidates. In general, anti-corruption communications campaigns – with anti-vote buying campaigns as a subset – tend to backfire, weakening faith in democratic institutions and their ability to combat corruption even further.

The conundrum of trying to combat vote buying by raising awareness of its scale and consequences was clearly illustrated in the recent elections in Moldova. Both the 2024 presidential and 2025 parliamentary elections took place amid allegations–and investigations–of widespread corruption and vote buying schemes, often linked to large-scale foreign interference intended to sway the country’s geopolitical alignment. These schemes included cash transfers and illicit financing using apps, virtual currency and Russian bank accounts, and fake grassroots organizing. Yet, despite the scale of these challenges, vote buying decreased significantly between the 2024 and 2025 elections. One reason for that progress was Moldova’s more deliberate effort to address electoral corruption, particularly through voter education and mobilization.

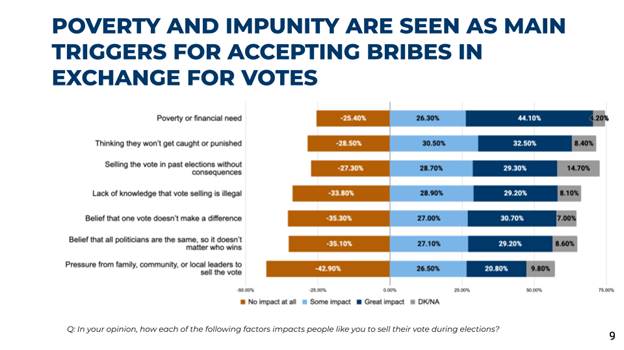

Understanding the triggers and underlying factors that enable vote buying is a crucial element in framing messages that resonate with people. Most respondents surveyed in 2025 identified economic vulnerability, institutional corruption, and entrenched social norms as the main drivers behind the practice. These perceptions were consistent with their views on how vote buying could be prevented: through improved living conditions, greater civic education, stricter sanctions, and institutional reforms that strengthen electoral integrity. Notably, more than 70 percent of respondents said they reject both vote buying and those who accept electoral bribes. While social desirability might play a role in shaping this answer, the messages piloted by NDI leveraged this finding to appeal to citizens’ moral responsibility and sense of integrity.

In constructing anti-vote buying messages, NDI also relied on previous research on anti-corruption messaging, which shows that effective communication should appeal to shared values and provide relatable and positive examples. It is especially important to avoid framing corruption as an insurmountable problem for that breeds despair. As respondents emphasized during the focus group discussions, messages are most impactful when they inspire agency, dignity, and a sense that change is possible. While respondents supported strict enforcement, they also expressed that punishment should target those who orchestrate vote buying schemes, rather than vulnerable citizens who should be met with compassion. In addition, participants favored responsibility-driven and empowering messages: concise, motivational slogans resonated most, while metaphors and threats proved less effective. For example, messages such as “In September, you are deciding your children’s future. Use your vote, don’t sell it,” and “Sometimes one vote can determine the result of the entire election – use yours wisely” gained the strongest traction among focus group participants. Demographic factors like age, education, language and geographic area played a significant role in how messages were received, underscoring the importance of tailoring and targeting communication to different audiences.

Ultimately, messaging alone cannot eliminate vote buying. In Moldova, communications campaigns by officials, institutions, nonprofit organizations, and media–many developed through the NDI program–worked best when paired with robust law enforcement. Well-crafted messages can reinforce, but never substitute for genuine institutional efforts to uphold electoral integrity and combat corruption.

Thanks for the article! Combining law enforcement with practical public awareness works better than threats to achieve real results.